Stories

E. Alfonso Romero-Sandoval – Research Sparks, Supports, and Perseverance

“One night, Jorge Lopez, my mentor in Guatemala during medical school, was playing the piano at a social gathering. While playing, he turned to me and said, ‘Can you imagine how many action potentials are triggered from my fingers and how many in your brain to interpret all this as music?’ I think that was the event that triggered my interest in understanding how the human body works,“ recalls E. Alfonso Romero-Sandoval. “After that, he was instrumental in helping me to obtain a scholarship to start my Ph.D. in Spain. My mentor in Spain, Juan Herrero, did the rest; and he showed me how to record and visualize action potentials to study pain.”

Romero-Sandoval, now an associate professor of anesthesiology at Wake Forest University School of Medicine, began his journey into pain research with sparks from these mentors, in medical school at Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala (Guatemala) and in graduate school at Universidad de Alcalà (Spain).

As a graduate student studying the biology of pain, Romero-Sandoval learned how the nociceptive system works—which is responsible for processing noxious stimuli, like injury and extreme heat or cold. “I was learning how to record neuronal activity, the electrical activity that travels from the toes to the brain to generate what we perceive as pain. I knew what this electrical activity meant and how this activity is generated at the molecular level. I had actually seen the shape of an action potential recording in my textbooks—however, when I saw a neuron’s live electrical activity, that was almost magical! Seeing the electrical activity in real-time was my very first impactful research experience,” explains Romero-Sandoval.

Since that pivotal experience, Romero-Sandoval has dedicated his career to pain research. His interests include cannabis research, gene therapy, inflammation research, and neuropathy, or nerve damage. The Romero-Sandoval lab studies the intersection between pain and inflammation following surgery and in neuropathic pain, as well as pain resulting from the effects of diabetes, or chemotherapy. In addition, the lab also examines the endocannabinoid system and pain, and the impact of the U.S. cannabis market on patient use. Specifically, this work focuses on examining the FDA response and regulation of advertisements for cannabidiol products and how to improve patient education on the benefits and risks of medicinal and recreational high potency cannabis products.

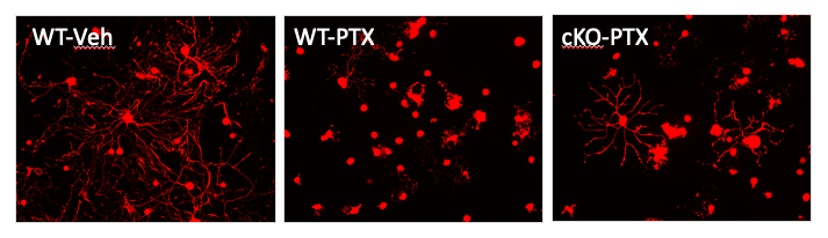

[Unpublished data]

As his research career has progressed, Romero-Sandoval finds excitement in continuing his work to discover molecular pathways than can serve as a biomarker for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy, peripheral pain caused by chemotherapy, as well as potential drug targets that can prevent such conditions. He sees these achievements as major accomplishments and looks forward to confirming multiple hypotheses as the work of his lab advances. Detecting neuropathy early on and finding new therapeutic targets can have an immense impact on preventative care for patients as well as treatment.

In reflecting on his research, Romero-Sandoval acknowledges an even greater satisfaction—that of seeing his trainees build their own legacies and advance in their career journeys. Nothing can equally compare to the joy he finds in mentorship and supporting the next generation of first-class researchers—building on the support he received from mentors.

In 2011, Romero-Sandoval was selected as a finalist for the Rita Allen Foundation Award in Pain. This was his second time applying for the award, and he remembers receiving the good news while on an overseas trip. “This was my first major grant and my second attempt. So, for me, the process was long.” Here, again his network of mentors and peers made an impact, “they encouraged me to try again and explained that perseverance was key to success. I tried again, and I got the RAF [Award in Pain]. The grant brought additional major funding in subsequent years and was a lesson of perseverance and resilience,” notes Romero-Sandoval.

“The intellectual excitement of having creative freedom in science produces a vibrant and engaging atmosphere in which extraordinary things happen.”

“While the RAF Award brought money to ramp up my research team and scientific ideas, the [Scholar community] activities—workshops, symposia, and gatherings—shaped my character as a scientist. More than that, the RAF Award influenced the expansion of my professional network in multiple dimensions, particularly because it enhanced the depth of my vision and mission of my research program. I learned that science is a good, intriguing idea to understand complex biological processes and improve health, and a vehicle to advance our communities and societies towards a civic goal of respect, unity, and trust,” reflects Romero-Sandoval.

Here, Romero-Sandoval provides his insights on the biggest challenges in his research, rapidly advancing technology, and joys beyond the lab.

What are the biggest challenges in your research?

The constant pressure of being well-funded and publishing impactful research to keep my lab active and productive. I think that constrains my freedom and creativity. I would like more time to develop bolder ideas. That is why the RAF Award is excellent: it allows you to be bold, risky, and adventurous! The intellectual excitement of having creative freedom in science produces a vibrant and engaging atmosphere in which extraordinary things happen.

We live in a time when technology is rapidly advancing. Can you speak to how that affects emerging science, and more specifically, how that might change your science and/or your approach to science?

I find this time extremely exciting because all the tools and technological advances could speed up the pace of discoveries and make us a better and healthier society. It is impossible to be an expert in multiple novel techniques or technologies; we are forced to reach out to other colleagues. And, I believe this is a fascinating catalyst for scientific integration and the creation of synergistic collaborations. So, novel and rapid technological advances can shape my research program by expanding my interactions and applying a more multidisciplinary approach to the questions I am trying to answer. However, it seems that the pace of technological advances is superior to our ethical understanding of the implications of their use.

What do you like to do when you are not in the lab?

I am a big soccer enthusiast. So, I play soccer every time I can. I love journalism, so I devote time to reading newspapers and watching or listening to interviews (I love the genre). I have filmed a documentary series in which I interview my aunts and uncles in Guatemala to preserve the historical memory of my family’s origins for the next generations. I love storytelling, and my aunts and uncles are great storytellers. I had to document that. So, when I have free time, I edit the videos to get a more polished final product.