Stories

Ted Price: Developing Non-opioid Therapeutics for Pain

“I remember realizing when I wanted to become a scientist, after watching Cosmos: A Personal Voyage,” says Ted Price, reflecting on his early-childhood watching of Carl Sagan’s award-winning PBS program. The show led Price to start reading popular-science books for kids and inspired his goal of becoming an astrophysicist. Although his parents were not scientists themselves, they supported his interests and were very engaged in his education during his childhood.

After high school, Price pursued his interest in astrophysics as an undergraduate at the University of Texas at Dallas, which had a well-recognized space-science research institute. But during his coursework, Price struggled to understand how math and the physical world connected. “If you want to be an astrophysicist, that’s not a very good sign for your future,” jokes Price. Fortunately, his faculty adviser, who had worked in the Apollo program, realized Price’s potential. The adviser suggested that he try a neuroscience class; UT Dallas had recently hired two new professors in the field. Price signed up for his first neuroscience lab class and was immediately delighted.

Price remembers his first research experience as a neuroscience student, conducting in vivo electrophysiology experiments. “We were doing two types of experiments in rats. It was really kind of amazing that we were able to do these things as undergraduate students in the laboratory. We studied circuit tracing with anterograde and retrograde tracers, and we were also doing in vivo electrophysiology in the hippocampus. One of the first experiments that I did as an undergraduate student was inducing long-term potentiation in the hippocampus by stimulating the perforant path. This is a classic kind of neuroscience experiment.”

In addition to electrophysiology, Price also had a positive experience working on the psychology of face perception with his research adviser, Alice O’Toole. “It was quite different from my emerging background in cellular neuroscience, but Alice was one of the first people tying the psychology of face perception to principles of how the brain functions. She used functional MRI and was really creative in the way that she designed experiments.”

Sometimes they would bring patients in, and we would get to hear their stories and ask them questions. That education had a huge impact on how I thought about how to build my career, and it also emphasized to me that the way we’re trying to approach pain therapeutically, right now, just doesn’t work.

Price was one of the first students to graduate with a bachelor’s degree in neuroscience from UT Dallas. After the diverse and exciting research experiences Price explored as an undergraduate, he was torn between choosing a graduate program focused on human perception and brain imaging, or the basic mechanisms underlying depression. Ultimately, he chose to go to the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio to work on basic neurobiology.

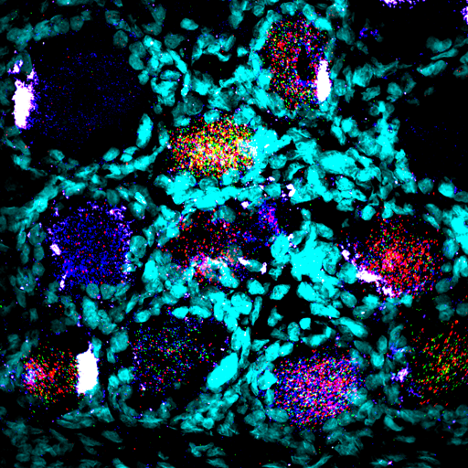

As a graduate student working with Chris Flores and Ken Hargreaves, he started to learn about cannabinoid pharmacology, specifically investigating how the endogenous cannabinoid system worked in the context of pain. “They both looked at the people who worked there as the most important part of their legacy and did an amazing job with helping us understand how the NIH works and how to get your research funded. That’s had a huge impact on me,” Price says.

Upon completing his graduate research, Price moved to McGill University for a postdoctoral fellowship working with Fernando Cervero. To this day, he is still awed by his experience at McGill—a mix of basic science, clinical work, and classes taught by some of the best physician-scientists. “We had these pain rounds where it was a mix of basic science and clinical work. Sometimes they would bring patients in, and we would get to hear their stories and ask them questions. That education had a huge impact on how I thought about how to build my career, and it also emphasized to me that the way we’re trying to approach pain therapeutically, right now, just doesn’t work. None of the clinical tools really have an impact on the underlying disease. It drove me to want to understand what drives the underlying disease that causes people to have severe chronic pain, in particular neuropathic pain, and also to be entrepreneurial about what we do and to develop therapeutics for clinical use.”

From McGill, Price was hired onto the faculty of the University of Arizona. There he focused his research on RNA localization as a mechanism for pain sensitization. But he had trouble securing grants—“I was really disappointed that my research was not getting a lot of traction,” Price recalls. All that changed once he became a Rita Allen Foundation Scholar in 2009. “I was quite stunned and extremely excited. It was a huge moment for me.” Several months after being selected as a Scholar, he received additional funding from the NIH. “I firmly believe that it was the endorsement of the Rita Allen Foundation that changed the way people viewed the work that we were doing. It had an absolutely huge impact,” says Price.

In addition to his work in the laboratory, Price has taken an active role in developing therapeutics by launching many companies, including: Ted’s Brain Science, CerSci Therapeutics, 4E Therapeutics, and Doloromics. “It became clear to me that if I was actually going to take the research that we were doing and turn it into something that was going to help patients, I would have to be involved in a major way in spinning it out of the university and into the private sector,” says Price. Ted’s Brain Science, which sells topical pain treatments, has been in business for three years and is one of the most rewarding parts of Price’s career. “I get emails on a regular basis about how much the product we created has helped [patients], and that really is amazing to me.” In addition, at CerSci Therapeutics he developed a compound with his team that was purchased by Acadia Pharma and is now in Phase 2 clinical trials. “It’s a non-opioid acute-pain drug, and if we’re successful it could be used for post-surgical pain. That could make it so that millions of people every year don’t have to be exposed to opioids to treat pain after surgery, and I think that has the potential to save tens of thousands of lives per year.”

Today, Price is the Ashbel Smith Professor in the School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences at the University of Texas at Dallas. Here, he shares a success story, advice for new Scholars, and a few thoughts on what he likes to do in his free time outside of the lab.

Can you share a recent success story?

We thought that translational regulation signaling was an underlying mechanism that causes the nervous system to change when animals or people develop neuropathic pain. While I don’t think we’ve discovered the one true mechanism—there may not be one true mechanism—we have discovered something that is pretty fundamentally important to how [neuropathic pain] progresses; and the cool thing about it is that it can be targeted with very specific pharmacological tools. If you hit those pharmacological targets for long enough, we’ve shown over and over again that we can reverse the underlying pathology. That gives me hope that it’s possible to produce so-called disease-modifying therapeutics for neuropathic pain, and maybe they will even cure neuropathic pain. So, I’d say that that’s our biggest success, and we’ve turned that into therapeutics that are in clinical development. We’ve developed this topical treatment that will probably not be something that can cure neuropathic pain, but it does seem to help a lot of people that have neuropathic pain, and we are developing more powerful, orally bioavailable drugs that are rapidly progressing toward clinical trials.

What is your advice for new Scholars coming into the field?

One of the most important things you can do is be true to your ideas. If you have a really exciting, transformative idea, you should go after it. I think a lot of people suffer from rejection of grants and papers, and I think a lot of people don’t realize that most of us have gone through that and that nobody is really successful right out of the box. We should be a little bit more open about how disheartening and almost even soul-crushing it can be to have setbacks. I do believe that eventually, people see the light on good ideas and that you’ll get the funding and be able to make it work. My first eight NIH grants were triaged—I really thought that the end was going to come early for me.

What do you like to do with your free time outside of the lab?

I try to play basketball as much as possible. Then I try to be with my kids as much as I can. We also really love to go to the national parks with our kids when we can get away. Glacier National Park is my favorite. The scope of the landscape, the lakes, and how they nestle into these amazing mountains—that place just totally blows my mind.

What book are you currently reading?

I just read The Autobiography of a Transgender Scientist, by Ben Barres. Barres was a professor at Stanford; he also happened to be transgender and recently died of pancreatic cancer. His lab made most of the fundamental discoveries on microglia. It’s a short autobiography. It’s beautifully written. It summarizes his life and his struggles as a transgender scientist and also the [research] of all the great people that he worked with; I just thought it was a beautiful book.

Any additional thoughts? I have learned so much at the Rita Allen Foundation Scholars meetings that I’ve gone to—the people I’ve met [in the field] and the people I’ve met who are outside the field, like Joe Palca, a science correspondent at NPR. I also have made great friends among the other Scholars. It’s had such a huge impact on everybody. I think it’s amazing how the Rita Allen Foundation has not only provided these wonderful opportunities, but also created this great family. It’s enriched my professional life tremendously.