Stories

A Public Lab Barnraising (Photo: Jeff Warren CC BY-SA)

Finding the Questions that Matter

How Public Lab is evaluating its pioneering model of community science

On April 20, 2010, an oil rig operated by BP in the Gulf of Mexico exploded, killing 11 people and beginning a leak that spilled an estimated 3.19 million barrels of oil into the Gulf by the time it was finally capped on July 15. It was the worst oil spill in U.S. history.

Shannon Dosemagen

(Photo: Nathan Dappen)

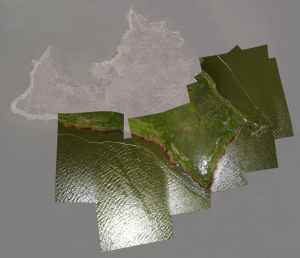

Public Lab coalesced in response to the spill, organizing under the banner of “Grassroots Mapping” at a time when no reliable official information was available about the extent of the spill. We used tethered kites and balloons to launch simple point-and-shoot cameras a thousand feet above the Gulf to capture images of the impact of the spill on places Gulf Coast residents like us cared about. The images were then digitally stitched into maps that were then shared internationally via the BBC, The New York Times and other news outlets, allowing residents to speak their truth about the impact of the spill.

Following the success of the oil spill mapping work, we wanted to continue. In fact, we wanted to think bigger about the scientific process itself. Science often is a closed loop, with little input from those outside of professional science. What if we brought it into the public realm? What if communities could collect and own data and use it to assert their interests? What if tools for scientific measurement could be easily obtained by people who wanted to collect information about their environment?

Aerial images of Wilkinson Bay, Louisiana, acquired by members of Public Lab in the wake of the 2010 BP oil spill

As we’ve grown and refined our model, we’ve centered our work on using science and science literacy as tools for civic participation and engagement. We want to inspire people to ask questions about the places they care about and help them answer those questions through the scientific process. We facilitate their exploration by creating access to low-cost tools, clear study designs and community workshops.

Community science is at the core of what Public Lab does. It encompasses scientific investigation led by communities, from start to finish, to address questions that they define.

We view community science as encompassing many different outcomes. Success can mean simply bringing a group together around similar questions, or it might mean pursuing changes in laws and regulation based on data that is collected. Our work revolves around supporting and meeting people where they are. We think about the information that is present but may need to be deciphered, what kinds of information could further support the questions that people ask, and how to build literacy as a key part of sharing information, so no one is left out of the process of scientific questioning.

As a grassroots organization, we’ve always recognized the importance of evaluating our model and thinking about what is working for people or where we may need to try something new. We understand that the quicker we identify successes and failures, the better equipped we are to respond by changing our designs and iterating on new ideas. However, with a small staff, capacity is always a question. Funding from Rita Allen has allowed us to test assumptions as early innovators in our space. We have been able to increase our outreach capabilities, be self-critical, test and fail.

Public Lab develops and sells low-cost, do-it-yourself environmental measurement tools. This spectrometry kit includes all the parts for a simple but powerful experimental tool for identifying contaminants in soil and water.

We’re now systematically thinking through what is working and how we can scale our model of deep community engagement. We’ve partnered with a brilliant environmental educator from UC-Davis, Heidi Ballard, who thinks critically about the space of science in, for and by the public. She has been able to see the unique challenges of evaluating a model like Public Lab’s.

During the first year of this project, we’ve been working on building a quantitative snapshot of Public Lab. Our initial set of questions numbered around 100—from questions about our events to the way that people moved through our online systems. Do more people first join the mailing list and then post a research note or vice versa? Do people who tweet to us about their projects go on to contribute a research note for the shared knowledge of the community? The questions were endless.

As we sorted through all the potential research questions, we started thinking about what was at the core of our questions about Public Lab. How could we measure the impact of deep, meaningful engagement in open science? Measuring that core theme has led us to begin asking questions that can’t be answered by looking at analytics, but by doing what we love most—talking and listening to people.

How do people share and receive knowledge and skills from each other? How do they apply their previous expertise and skills to new and often unexpected areas? How do they bring what they learn while interacting with the Public Lab community into their social networks elsewhere? It’s been fascinating to think through questions that will get to the heart of what we do.

How could we measure the impact of deep, meaningful engagement in open science? Measuring that core theme has led us to begin asking questions that can’t be answered by looking at analytics, but by doing what we love most—talking and listening to people.

We’ve approached evaluation as a collaborative project across Public Lab, asking people about what tools they can use to contribute information about impact, and working with organizers who are interested in doing community evaluation hand-in-hand with this project. Although this process of engaged asking has sometimes meant an elongated timeline, we hope it will shape a stronger evaluation model. We’re also bringing together communities within Public Lab that often operate independently—such as engineer/maker/hacker/science-focused people and social justice/community organizing/advocacy-minded people.

Public Lab wouldn’t be where it is today if, with the support of our partners, we hadn’t been able to take risks, push at the boundaries of what’s been done before, and learn from both our successes and failures. We’re excited by this opportunity to ask new questions, test assumptions, evaluate our own model and share what we are learning—the good and the not-so-good—with everyone.

Shannon Dosemagen is cofounder and Executive Director of Public Lab.